DIRITTI

Life Beyond the Pandemic

Something is moving in the rubble of the pandemic. We are separate, but today more than before joined by the desire to change everything. A devastating event like Covid-19 requires powerful responses and boundless ambition

This collective text, by the feminist and transfeminist assembly Non Una di Meno Roma, part of the larger Italian movement Non Una di Meno, was circulated in late April, during the phase-1 of the Covid-19 lockdown imposed nationwide by the Italian government. Over the past four years, Non Una di Meno has been campaigning to end male violence against women and connecting it to the violence of heteronormativity, precarious labour, racism and the European regimes of border control. A key tool of struggle has been the feminist strike from reproductive and productive labour, organised at the transnational level on March 8th since 2017.

Something is moving in the ruins of the pandemic. We are still physically distanced and yet, now more than ever, the desire to transform everything is bringing us together. An event as devastating as Covid-19 calls for powerful responses and unbridled ambition. The pandemic has made clear that the reproduction of life is incompatible with the neoliberal project to apply the market rationale to every aspect of our existence. In order to orient ourselves, we turn to feminist and transfeminist knowledge and practices that have focused on social reproduction as the key battle field. We build on a collective, situated self, one that shifts through transversal alliances, always taking on new shapes. In fact, if the present is catastrophic, the future is unwritten and our struggles have the potential to create new modes of living together after the pandemic.

To stir up a powerful response to devastating events, we turn to the “arcane of reproduction”, that is, all those activities that regenerate human life in a given historical and social formation.

These include not only the reproduction of generations, the affective and bodily care of everyone, including adults, children and the elderly, but also the care of spaces and the household, education, access to culture, services, leisure and social relations. Feminist movements have unveiled the centrality of reproductive labour and defined it as the condition of existence of the whole of society, its persistence in time.

In the 1970s, the campaign Wages for Housework demonstrated that the transition to capitalism, starting from the dawn of modernity, was made possible by the invisibilisation, naturalisation and devaluation of reproductive labour. Without the domestic and care work that allowed the subsistence of (male) workers, there would have been no labour force. Without labour force there would have been neither factories nor profit. And yet, reproduction has never been acknowledged as work. On the contrary, it has been ascribed to the sphere of natural resources available to appropriation. This has served the purpose to legitimise an immense extortion of wealth. This is the thread linking women’s unpaid work in the household to the expropriation of the planet’s resources.

As Black and anti-racist feminists have emphasised, domestic labour, reproductive labour and resource expropriation have always been divided along the colour line. Today, migrant and racialised women continue to bear to brunt of exhausting care work inside and outside the family. Indigenous land and populations continue to be plundered by capitalist predatory violence. These are the afterlives of slavery and coloniality.

To stir up a powerful response to devastating events, we look at the reorganisation of reproduction in neoliberal societies before and after Covid-19.

The neoliberal model is rooted in the celebration of the market and social competition, in individual responsibilities in adapting to risk. It has demanded the privatisation and erosion of the public institutions and programs that contributed to partially redistribute reproductive and care work in the 20th century. Additionally, over the last fifty years, the dismantling of the welfare state has gone hand in hand with a radical reconfiguration of labour, known as “feminisation of work.” By this we mean flexibility, total availability and the exploitation and valorisation of relational, linguistic and care capacities. If, on the one hand, reproduction has become immediately productive, on the other hand, value chains feed on the exploitation of gendered, racialised and queer subjectivities, thus rendering the lives of entire generations precarious.

With the outbreak of the pandemic, the fragility of the reproductive and care structures, starting from the healthcare system, has become evident. In Italy, the last decade of austerity and neoliberal policies have meant the disappearance of 70,000 hospital beds, 359 wards and entire hospitals. The most brutal, ruinous effects of these measures is now visible to all. The pandemic has highlighted the centrality of social reproduction but also its profound crisis. As some say, the virus does not discriminate between social classes. But class, race, ability and age discriminations manifest themselves in the impossibility of accessing healthcare. Some lives enjoy the right to assistance and care, others do not. There is no such a thing as “bare life” – there are lives marked and stigmatised by class, gender, sexuality, geographical positioning, disability and age. There are bodies suffering from isolation, and others that have made the quarantine possible, because they have never stopped working, inside and outside the household. These are health workers, janitors, domestic and care workers, mothers who care for their children and daughters who care for elderly parents.

To stir up a powerful response to devastating events, we start from the home, the main place of exploitation of women, but also the first space of feminist conflict. We have stayed in for weeks, but not all in the same way.

There are those who don’t even have a home. Homes reflect a series of inequalities. For some, the home is no refuge from a pandemic, but a place of oppression, threat, violence, even femicide. For many domestic and care workers, (the) homes (of others) are still the place of exploited and unrecognised work. This was confirmed, once again, by the institutions: the “Cura Italia” decree left out care workers who were not able to benefit from mechanism of income guarantee and measures for health protection. 80% of the care workers in Italy are migrant – they amount to more than one million. For these people losing their job has also meant losing a place to live, and being held hostage by an exploitation system that links the possibility to accept or refuse a job to one’s residence permit.

We start from homes as a battleground, as a place to shape new (but also old) alliances, seditious and intersectional coalitions. Time dedicated to care is a time of conflict and imagination. We take advantage of the difficulties we are experiencing: homes, which are now also offices, school and university classrooms, an area where production and reproduction can no longer be distinguished, will have to change radically.

To stir up a powerful response to devastating events, we look to education and knowledge networks.

For years neoliberalism has starved schools and universities. Since the beginning of the pandemic, teaching has been carried out online, which has, on the one hand, provided “platform capitalism” with new opportunities to appropriate knowledge – always produced in a cooperative way –, on the other, it has accentuated social differences and discrimination based on ability. Decision-makers, both experts and politicians, have no regard for education as relationship and care, they celebrate agile and smart working. But as teachers have been denouncing, smart working is yet another form of exploitation, as well as a profound discrimination against those who carry the burden of caring for children, the elderly, the disabled.

Children, teenagers and kids are paying a very high price. The transmission of knowledge cannot be separated from proximity to peers and teachers, which plays a fundamental role in building autonomous relationships, away from the family. The impossibility of proximity will have serious consequences, from an emotional and social point of view, but also from a political one: schools and universities are places where the young discover and nourish both erotic and political passions.

Right from the start the issue of schools led to the organisation of many territorial solidarity networks, from those working to bridge the digital divide, to those helping to meet primary needs. Practises of mutualism cannot replace institutional interventions, but they indicate the way towards the construction of a new common space, beyond the State, but also beyond the family, which can no longer be viewed as reference point for the distribution of income and resources.

To stir up a powerful response to devastating events, we claim that freedom of movement must be at the centre of the reflection on social reproduction.

During the very first days of the emergency it became clear that the food supply chain depends on migrant workers, who are employed in agriculture, logistics, distribution, services. Many refused to work due to a lack of safety conditions, while others were blocked by the restrictions on movement between states imposed to contain the pandemic. That same border system, which causes daily deaths among migrant women and men, forces us to consider the link between freedom of movement and the conditions that make the reproduction of life possible.

In migrant detention centres, from Ponte Galeria to Gradisca d’Isonzo, in the reception created for the containment of asylum seekers, in the slums and informal occupations, which compensate for the absence of reception and housing, the restrictions on movement imposed during the social and political emergency Covid-19, are not measures that block the pandemic, rather, they multiply the obstacles to freedom to save oneself. The same can be said of the shameful decree that declared Italy is an “unsafe port”, or of agreements that block migrants in Libya or on Greek islands. In addition to numerous non- essential factories, it was precisely the detention centres as well as the prisons, that remained in full operation, places whose function it is to reproduce bodies intended for exploitation.

The massacres taking place in the Mediterranean, for which the pandemic has provided a new excuse, show us that policies against freedom of movement are policies of death. To stir up a powerful response it is necessary to put freedom of movement at the centre of our battles and around this claim work for a new and universal access to rights, welfare and income.

To stir up a powerful response to devastating events, we look at the socio-ecological dimensions of reproduction. The nexus between social and ecological reproduction is not new. Together with women’s work, industrial capitalism has appropriated the biosphere as a source of matter and energy.

Reproductive activities and the biosphere have been reduced to free resources to fuel a mode of production driven by the imperatives of profit and growth.

Today, the collapse of healthcare systems follows that of ecosystems. These processes have created the conditions for the pandemic and its devastating consequences. The out-of-control expansion of deforestation, intensive agriculture, industrial farming and urbanisation have created opportunities for zoonotic spillovers. After finding a new host species, the Sars-Covid-2 virus has travelled across the circuits of the globalised economy. The coronavirus, as some studies suggest, drifts through particles of air pollution and is more easily transmitted in highly polluted, densely populated areas such as Wuhan and the flat plain of the Po Valley. In Italy, the infection spread in workplaces that were shut down too late or reopened too early. Contagion worsened in a healthcare system weakened by budget cuts and privatisations.

The pandemic has confirmed what feminist and socio-ecological conflicts have been saying for a while: the connections between social and ecological reproduction can no longer be ignored or dismissed as secondary. Our wager is to extend care from singular bodies to that which allows them to persist: relations, ecosystems, the biosphere, the planet itself. This is the ground of encounter, and possible convergence, between feminist, transfeminist and ecological movements.

To stir up a powerful response to devastating events a radical redistribution of wealth is needed.

While in Europe and at a global level decision-makers clash over the tools needed to manage a massive economic and health crisis, what is starting to emerge is that States and economic-financial institutions will inevitably have to start re-investing in social spending. The point is how. How consistent will public funding be, and who will benefit from it? Will this investment continue to be based on the mechanism of debt?

Emergency measures are not enough. Many are now arguing in favour of a basic income, a care or a quarantine income. Similarly, we are convinced that a structural and redistributive measure is needed. For years, in fact, we have been claiming an income of self-determination: universal and unconditional, addressed to individuals and not to the family, not connected to work, citizenship and conditions of residence, which must guarantee economic autonomy, an instrument to escape from gender violence, from exploitation, of labour and of the ecosystem. We claim a self-determination income together with the European minimum wage, to prevent the former from becoming a tool in the hands of companies and employers aiming at reducing wages, to combat ridiculously low wages, and wage disparities between women and men, natives and migrants.

We want welfare institutions to be structurally refinanced and rendered universal, we want free and supportive institutions to which everyone may have access: a public and laic healthcare system, more territorial clinics, continuous hiring and permanent contracts for staff; investment in school, training and research; childcare services; support and care for the most vulnerable; guarantee of the right to housing; social security.

It is important to stress that struggles for welfare, other than being struggles for the redistribution of wealth, are struggles for democracy, for the democratic reappropriation of social infrastructures. To defend the public means to imagine common institutions and freedom beyond the State.

To stir up a potent response to devastating events, it is crucial to create new alliances of care in common.

“Flatten the curve, increase the care” is the slogan of the art and activist collective Pirate Care. In our view, it conveys the meaning of the feminist wager: containing the contagion is not enough, we need struggles for reconfiguring the infrastructures of care, taking control away from market forces. This is how the bodies that today are more exposed to the pandemic’s deadly effects will enjoy the protection that has been a privilege for few.

The mutual-aid networks operating in many Italian cities point in that directions: they have developed modes of caring from below that draw attention beyond individuals and towards communities. Consider, for example, the solidarity networks among and for sex workers that have been able to overcome the barriers of stigmatisation and criminalisation, standing with those who are more exposed to contagion and exploitation. Or think about how, in Rome as well as other urban centres, domestic violence shelters have continued to operate remotely to support women who are quarantined with abusive partners. In the same vein, radical unions and other organisations have provided legal support and facilitated access to social programs to precarious, migrant and informal workers and the unemployed. Solidarity brigades linked to squats and neighbourhood initiatives have mobilised for home delivery and distribution of groceries to those in need.

Care has thus become an experimental field. Moving beyond the enclosed space of the hospital, which, to be sure, is essential at the time of such a sanitary emergency, care has become a matter of diffuse and promiscuous relations, nurtured by networks of intimacy that do not coincide with biological kinship. We need to rethink the forms and the institutions of care beyond heteronormative and patriarchal models that view the individual and the family as the basic units of society. We need to rethink our life in common, bringing down once and for all the violence of the neoliberal model.

The rising struggles demand strength, determination and creativity. In the past few years we opened new paths with the resignification of the strike as a tool of struggle. This process is still ongoing and points in a direction that needs further exploration. Workers’ strikes, as well as the riots that broke out in prison at the peak of the Covid-19 emergency, have shown just that.

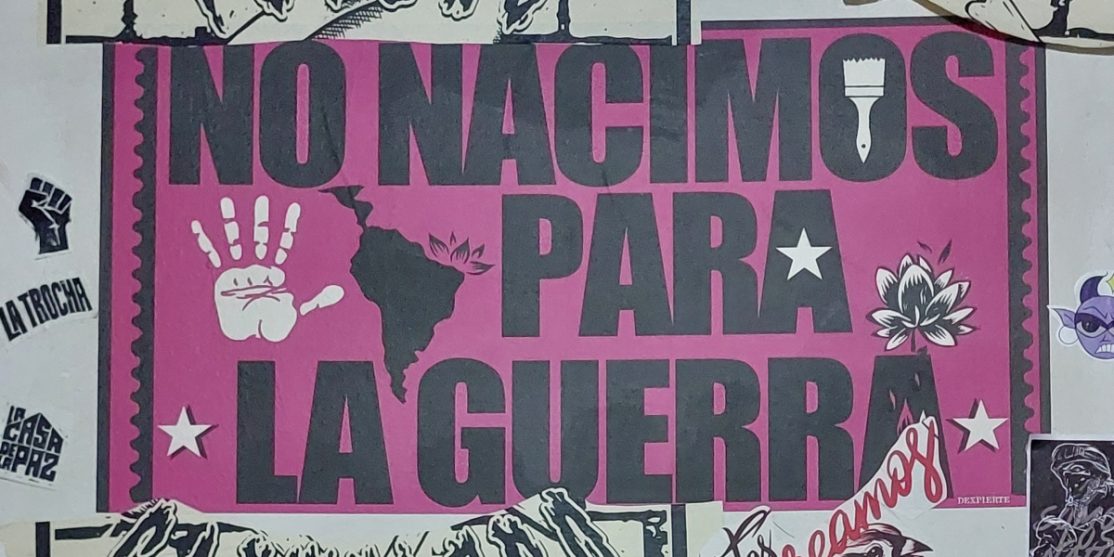

Now more than ever it is time to struggle for the redistribution of that same wealth that for centuries has been expropriated from women. Inspired by the Argentinean feminists who marched before the pandemic hit the country, this is the time to collectively shout “The debt is owed to us!” and “We want to be alive, free, debt free!”.

About the authors:

Non Una di Meno Roma is a feminist assembly based in Rome. Part of the larger network Non Una di Meno, the assembly has been meeting since 2016. It brings together a large, shifting group of feminist and transfeminist activists and collectives, including domestic violence shelters, students, researchers, feminist attorneys, precarious workers, cultural agitators, radical union activists and indomitable spirits. You can contact us on Facebook (facebook.com/nonunadimenoroma) or write to nonunadimenoroma AT gmail.com.

Cover photo by Cinzia Barra

Translated by Emma Gainsforth and Miriam Tola for Interface Journal