approfondimenti

MONDO

Back to Where it Started? Turkey’s Local Elections Might Suggest a Cracking Hegemony

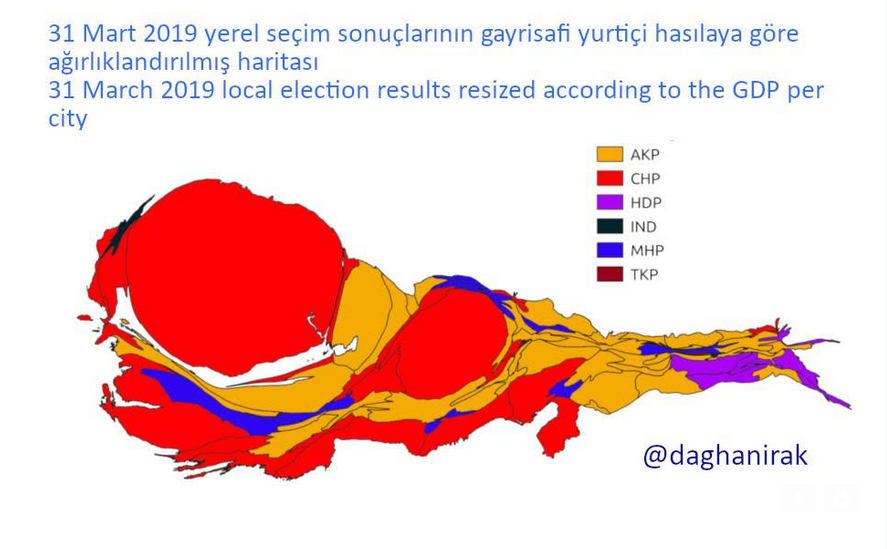

The victory of the alliance lead by the Republican People’s Party (CHP) at the recent municipality elections gave to the oppositions the local government of many of the most important cities of Turkey, among which Istanbul with the exciting victory of Ekrem İmamoğlu. It could be the beginning of the end of the political-economic hegemony of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, started in 1994 precisely in Istanbul, that is now encountering quite few obstacles, starting with one of the most difficult economic crisis in Turkey’s recent history

In 1994, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan had shocked Turkey’s establishment parties by winning the local elections in Istanbul, receiving %25 of votes in a four-candidate race and becoming Istanbul’s Metropolitan Municipal Mayor. That same day, Turkey’s capital Ankara was won by Erdoğan’s fellow partisan Melih Gökçek, alongside many districts across Turkey. This was a time when, in the framework of Turkey’s EU-accession ambitions, a new discourse of decentralist democracy and neoliberal reforms, elected municipal governor was morphing into a more powerful position than earlier. For un uninterrupted 25-years since 1994, metropolitan municipalities of Istanbul and Ankara in particular, but municipal power more largely, have functioned as the epicenter for an economic and political solidarity network which supported Erdoğan’s growth from an outside challenger to a regime-changing strongman. Erdoğan famously said in a speech to his cadres, “if Istanbul stumbles, we will fall.” Istanbul is home to more than %30 of Turkey’s GDP. Istanbul, Ankara and Izmir combined make almost %50.

Erdoğan established his charismatic repertoire of rule first as the mayor of Istanbul (1994-1998). This repertoire gradually morphed into Turkey’s new regime. The main pillars of this new hegemony were widening legal authority for municipal governments to act like corporations and provide urban services more efficiently than before, building consent among mid- to low-income urban neighborhoods; a subsequent class of upwardly mobile and politically motivated urban contractors personally indebted and loyal to Erdoğan’s party apparatus; and the unwritten rule that these businessmen who accumulate capital in this way are expected to donate large sums to politically motivated civil society institutions, most critically, religious foundations governed by Erdoğan’s nuclear family and kinship circle. During the 17-year, uninterrupted one-party government under Erdoğan since 2002, this network spanning elected local and national scales, with Erdoğan’s personal charisma at the top, has helped Erdoğan outgrow his rivals despite many challenges. In 2013, a new law of Metropolitan Municipalities further widened the scope of municipal power, new articles allowing direct cash transfers from municipal budgets to civil society, including to sports clubs. In the ongoing 2018-2019 football season, the newly founded and barely supported Başakşehir is about to win Turkey’s Serie A. Başakşehir was originally a sport club owned by Istanbul’s Metropolitan Municipality and is now personally owned by a kinsman of Erdoğan and managers of municipal corporations. Başakşehir’s rise in football is an apt illustration of contemporary Turkey: a new champion supported by an exclusive kinship clique of municipal riches, but risks losing popularity.

Immediately after elections, Ankara’s and Istanbul’s new mayors are already considering stopping cash flows to politically chosen civil society and investigate previous corruption. At stake in local elections, therefore, is the possibility of stopping critical urban markets/networks from sustaining Erdoğan’s partisan hegemony. This is why, for the 17 days following the local elections on 31 March 2019, Erdoğanist cadres in Istanbul did everything at their disposal to reverse the initially announced results of defeat. Nevertheless, after the recounting of hundreds of thousands of ballots, Istanbul Board of Elections refused the appeals for further recounts and gave the opposition candidate the mandate. The new mayor Ekrem İmamoğlu won the close race with almost %49 of the votes, 13000 more than his Erdoğanist rival. In 2014, the gap was almost 700.000 votes in the opposite direction. An appeal to the National Board of Elections is on its way, which asks the national board to overrule the provincial board and rule a re-election on June 2. The current atmosphere suggests the results are to stay, however. In addition to Istanbul and Ankara, large cities in the Southern coast such as Antalya, Mersin, and Adana, also swung to the opposition. It’s a clear, nationwide victory for the oppositional alliance.

This electoral victory was possible thanks to an unorthodox alliance among the three major parties opposing Erdoğan, who successfully mobilized their bases to vote for a shared candidate in critical metropolises and persuaded a necessary number of swing voters. Let me briefly explain this unprecedented scenario. Following the camps which consolidated before the presidential elections in June 2018, four of Turkey’s five major parties are today grouped in two strategic alliances, despite retaining their autonomous party structures. The two alliances name themselves with barely distinguishable epithets. One the one side is the People Alliance (Cumhur İttifakı), which consists of Erdoğan’s Justice and Development Party (AKP) and the far-right Nationalist Movement Party (MHP), which ran a fearmongering electoral campaign based on the discourse of “state survival,” underlining the necessity of political stability against terrorist and geopolitical threats to the nation. On the opposing side is the Nation Alliance (Millet İttifakı), of mainly two parties, headed by the secular-nationalist/social democrat Republican People’s Party (CHP). CHP allied with the Good Party (IYIP), a new actor that split off from the MHP in 2017 and attempts to organize Turkey’s anti-Erdoğanist center-right elements into a centrist party. IYIP aims to revive the tradition of secularist center-right parties that had dominated Turkey’s electoral races before Erdoğan between 1960 and 2000. In many cities, IYIP relies on the traditional center-right strategy of being represented by notable members of the Chamber of Commerce and Industry, who are disillusioned by Erdoğan. In 2018 general elections, IYIP stole a good number of votes from Erdoğan and received %10 of votes and 43 seats in the parliament, mostly by focusing on the economy’s mismanagement.

Outside these two Alliances is the party championing Kurdish civil rights and decentralization, Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP), which strategists are accurately calling ‘the kingmaker’ of this local election. Despite not being formally affiliated with the oppositional Nation Alliance, HDP made a concerted effort to mobilize its supporters to vote for candidates fielded by the Nation Alliance and did not field competing candidates in Istanbul, Ankara, Adana, Mersin and Antalya. Days before the elections, HDP’s charismatic but imprisoned leader Selahattin Demirtaş’ official account tweeted to discourage HDP voters from boycotting the elections and motivated the party’s base to vote against Erdoğan. In metropolises housing significant Kurdish demographics, HDP’s votes range between %5 to %15, a decisive sum for the electoral math. This electoral alignment had first emerged in opposition to the constitutional amendments put to vote in April 2017, before which I also wrote a reflection for Dinamopress.

When this unofficial cooperation was obvious to the public opinion despite efforts by the CHP-IYIP to play it down and avoid the stigma of being associated with the HDP, Erdoğan reverted to scapegoating the HDP, the non-kosher for Turkish nationalism. In effect, Erdoğan called almost %50 of Turkey’s voters terrorists, in an attempt to dissuade swing voters from standing side by side with the HDP. Erdoğan termed the opposition, the abased alliance (zillet ittifakı), punning the opposition’s millet ittifakı. The most promising result is the backlash against this blackmail. It suggests that enough many voters are concretely dissatisfied with Erdoğan’s rule, particularly the economic crisis, and can call his bluffs. Nevertheless, if this temporary electoral cooperation has any chance of further developing into a reliable platform, it needs to be equipped with persuasive political concepts and a corresponding program that not only calls bluffs but is able to set up a new political game. Turkey’s new presidential regime established by the plebiscite in April 2017 rules out coalition governments and weakens the power of the legislative against the executive president. Given that the system is here to stay in the short-run, it forces challengers to a bipartisan mode of strategizing and necessitates alliances in general elections, the next one scheduled for 2023.

This is why the question of whether or how HDP will affiliate with the oppositional front will be significant. HDP proved its legitimacy in the eyes of Kurdish voters and once again won all metropolises in its home region. However, contrary to the brave stance by the Istanbul Board of Elections against pressures, several district boards of elections in Kurdish-majority provinces denied HDP-affiliated winners the mandate to govern and declared AKP-affiliated runners-up official mayors. The national public sphere is often less responsive to such systematic illegality in Kurdish areas while more readily so against unfair treatment in Istanbul. This reaffirms the deep-reaching political double standards in Turkey’s non-Kurdish and Kurdish regions. Some critics will go as far as to essentialize such discriminatory reflexes of Turkey’s state apparatus as “Turkey’s DNA,” given the systematicity and consistency with which parties championing Kurdish civil rights have been constitutionally criminalized in Turkey’s parliamentary history, beginning with the closing of Turkey’s first left-wing parliamentary party, Turkish Labor Party (1961-1971), which had programmatically argued for the recognition of a Kurdish people within Turkey’s constituency and expanded the meaning of Turkey’s ‘Eastern Question.’ Kurdish parties have frequently been constitutionally banned and/or restricted. HDP’s charismatic young ex-leader Demirtaş, alongside other HDP-affiliated municipal mayors, is currently in prison. Erdoğan will likely attempt to remove elected Kurdish mayors and appoint his cronies in their place by executive decrees, a strategy he employed before.

If a substantive oppositional front is to be lasting, the CHP and IYIP will need to invent a persuasive rhetoric of democratic legitimacy which accommodates due criticisms of unfair treatment against Kurdish representatives without alienating the swing voters. This is the only way to legitimately encourage Kurdish participation in a nationwide coalition and take the temporary electoral cooperation to a next level for a post-Erdoğanist Turkey. Despite minor acts of electoral reciprocity between HDP and CHP in the last two elections, HDP is stigmatized as ‘the parliamentary wing of the PKK,’ which poses and will pose a barrier for sustaining electoral solidarity across Turkey’s fault lines. There are no ready-made bridges to cross such a structural precipice, but there emerged a new political feeling which can nurture a mutually agreeable program against Erdoğan’s one-man rule.

There are signs that the CHP has become more open to democratic conceptions of the Republic in recent years. Combined with unprecedented victories owing to HDP-voters, this can encourage the party to engage the Kurdish question with more confidence. In Izmir and Istanbul’s Kadıköy district, CHP’s newly elected mayors belong to an explicitly social democratic tradition, considered the party’s leftish-wing. In Istanbul, CHP’s local party organization is headed by Canan Kaftancıoğlu, a critical figure who endured harassment campaigns by the party’s nationalistic factions but proved critical in ensuring CHP’s victory in Istanbul. The growth of this trend is associated with the after effects of the Gezi Park Uprising in 2013, which is interpreted to have encouraged CHP’s younger cadres towards more democratic concepts of the Republic. It’s important to keep in mind that despite older generations, younger CHP cadres have lived all their lives under Erdoğan’s rule and prioritize change and freedom over nostalgia for a bygone Turkey. A critical message of the elections is that giving in to Erdoğan’s conservative-nationalist blackmail is not the only option available to CHP, to which the party succumbed more than once in the past. Prominent HDP representatives also implied openness to solidarity, including a practical suggestion to sign a friendship agreement between Istanbul and Kars municipalities, the latter having swung to HDP. Demirtaş recently wrote an op-ed for the Washington Post, celebrating the electoral cooperation which proved successful. He wrote: “The members of the HDP and the Kurds of Turkey will always be ready for peace. I believe we will be successful. We will create a country with a strong democracy and economy by bringing together all factions of our society. The March 31 elections have shown us the way.”[1]Time will tell how possible it is to walk this tense way.

In Turkey’s political system, municipal power can function as a site for experimenting with democratic practices of governance and testing their potentials and limitations. Many interpret municipal governors to be face-to-face with constituencies compared to the unpopular politicking that dominates general elections. Municipalities are thus a good platform for building trust and political momentum. This is the first time CHP will govern so many critical metropolises and this is thanks to a new strategy of selecting candidates, which prioritized figures like İmamoğlu, who established reputations as trusted local governors during their terms as district mayors in the metropolises they will now govern. The idea of “testing democratic concepts” is explicitly uttered by İmamoğlu, almost word by word, in the first interview he gave to the press, notably to Rudaw, the Kurdish media headquartered in Iraqi Kurdistan.[2]If young mayors like İmamoğlu limit their mission to cutting cash flows to Erdoğan’s civilian networks, they’ll run the risk of being perceived as solely revanchist. Unless they can validate democratic promises and establish trust with communities wider than their own voters, Turkey will revert back to a cycle of revanchism. It’s important to keep in mind that Istanbul was won by a mere 13000 votes and the Erdoğan-led People Alliance collected more votes than the opposition when aggregated nationally. Occupying the seat of a very capable presidential throne, Erdoğan will do everything he can to financially and bureaucratically strangle municipal governors. How the opposition will react and how these conflicts will be interpreted by the electorate should define the course of politics.

İmamoğlu so far sounds acutely aware of the challenges ahead. His first policy was to reduce the price of student passes for public transportation by almost %50, a social democratic approach to municipal government which can expand his appeal as well as that of CHP’s. In his public celebration, he mentioned Kurds and Christian minorities as fundamental constituents of Istanbul. In his interview with Rudaw, he talks about municipalities sponsoring Kurdish and Arabic language instruction. He employed a rarely used historical narrative by referring to Turkey’s 145-year long struggle for democracy, tracing his political horizon not to the Atatürkist foundation, as CHP often does, but to the earlier but failed initiatives for a pre-nationalist Ottoman constitutionalism, which has long been the historiographical turf of Turkey’s liberals. He also speaks highly about HDP’s imprisoned leader Demirtaş as “having established a political tone of peaceful and universal values” and calls out the political motivation behind his imprisonment. Pundits often underline İmamoğlu’s similarities to Demirtaş in terms of his age and composed demeanor. All of these so far suggest an authentic and proactive figure who will now govern Istanbul and is aware that all of Turkey’s political contradictions manifest themselves materially in the gigantic city and that Istanbul is a good testing field for experimenting with new political concepts. Istanbul’s municipal life expands socially to every region of Turkey and beyond, through the immigrant residents’ diasporic links. This is why İmamoğlu, barely known to the public few months ago, is already hailed as a potential presidential candidate for 2023.

[1]Selahattin Demirtaş, “I’m in prison. But my party still scored big in Turkey’s elections.” Washington Post. 19 April 2019. https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2019/04/19/im-prison-my-party-still-scored-big-turkeys-elections

[2]The English version can be read here. “Istanbul’s new mayor vows to ‘eradicate partisanship.’ Rudaw. 18 April 2019. http://www.rudaw.net/english/interview/18042019